The United States was still reeling from the losses of the Great War and from the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic as 1920 approached.

The mood in the country was changing, and the political arena with it.

But the country was about to see another significant change that would give birth to “Blind Pigs” and “Blind Tigers,” and the nation would never be the same!

Early Momentum

The origins of the anti-alcohol sentiment in America date back to the colonial era, but the voices of protest were seldom heard.

It wasn’t until the 19th century that the movement began to gain traction.

The American Temperance Society was formed in February 1826 and was the first significant organized attempt to start a temperance movement. It started small but quickly gained momentum. Within 10 years, the organization had grown from a few local chapters to over 8,000 chapters and over 2.5 million members nationwide, who had taken the Society pledge to abstain from alcohol.

The movement was fostered by nationwide reports of rampant alcohol abuse that were felt to be responsible for the surge of domestic violence, child abandonment, drunkenness in the workplace, and squandering.

The cause was embraced by numerous religious organizations and churches that viewed alcohol consumption as a moral sin that threatened countless families and the fate of the nation.

Throughout the 1800s, the movement continued to gain momentum. In the post-Civil War era, more and more Americans began flocking to the “Dry Movement.” The end of the war saw a substantial growth of bars and saloons, as the country tried to heal and begin its expansion west.

The Dry Movement gains momentum

Toward the end of the 19th century, another temperance group emerged and quickly gained traction among men. The Anti-Saloon League (ASL) took their protest to local and state governments.

Their tactics included strong lobbying campaigns. The ASL pushed out pamphlets, broadsides, and newspaper ads that touted the evils of alcohol and demanded the cessation of sales. They publicly derided politicians who did not support the movement and chose candidates to run against them who did. They were very successful in their efforts.

One of the Temperance League’s more aggressive members was a Kansas woman named Carrie Nation. She gained notoriety for openly protesting by entering bars and preaching and singing hymns to the patrons.

She didn’t feel those simple actions were enough though, and her tactics quickly radicalized into throwing rocks through saloon windows and at bar patrons.

She was supported by her husband, David, who was also a fanatical supporter of the Dry Movement.

After an incident in Wichita, her husband half-jokingly suggested she might try using a hatchet to effect maximum damage.

She was soon being arrested for brandishing a hatchet and destroying the bars and alcohol stores in several bars and saloons.

Arrested for her many attacks, Carrie was repeatedly bailed out by her husband, who was raising money for the movement by giving lectures on the evils of alcohol and even sold small stick pin miniature hatchets.

Most towns and counties were reluctant to prosecute her because of the growing strength of anti-alcohol sentiments sweeping the country.

The end of the 19th century saw an increasing number of states that already had statutes banning the sale of beer and spirits.

The Great War

The dawn of the 20th century afforded many new opportunities for the support of the growing prohibition movement.

When the U.S. entered into World War I, the movement saw it as an opportunity to further teach the evils of alcohol. Since most large breweries in the country were German owned and operated, their nationality was used against them by claiming that supporting the consumption of their products was treasonous.

The federal government used World War I as an opportunity to initiate laws that banned the manufacture of beers and liquors, citing that the crops were better needed to support the troops and the war effort against the “Huns.”

The precedent was set

With the end of World War I, the anti-alcohol organizations kept up the pressure on local and state politicians for a continued ban on beer and spirits.

There had been a shift in feelings at the federal level. It was felt that there were enough Congressmen and Senators in place to create federal law that would address the concerns on a national level.

Wayne Wheeler of the Anti-Saloon League wrote a draft bill titled the “Volstead Act.” It was named for Andrew Volstead, who was the chairman of the powerful House Judiciary Committee.

Volstead would champion the bill through the House and Senate.

The bill was pushed through and was initially vetoed by President Woodrow Wilson, who did not support the legislation. But his veto was overridden by a House vote of 68% in favor and 76% in the Senate and was quickly ratified by 46 of the 48 states on January 16, 1919.

Amendment XVIII

The 18th Amendment became an enforceable law on January 17, 1920.

The new amendment made the importation, sale, and transportation of alcohol illegal but did not address personal and medical consumption.

Wines and hard ciders could be made from fruit at home, but beer and spirits were completely banned.

In anticipation of the January 17 date, the country saw a run on alcohol purchases. Clubs and organizations began stockpiling while vendors embarked on marketing campaigns encouraging the public to “get theirs” before the ban on sales took effect.

There were several loopholes in the new law. One of the biggest was the ability for alcohol to be “prescribed” for medicinal purposes covering a variety of ailments.

It was estimated that within six months, over 57,000 licenses were issued to doctors and pharmacists to prescribe alcohol remedies.

The ban was welcomed by many, but there were many who were not happy with the new law.

It wasn’t long after Prohibition took effect that the country saw a rise in illegal activities relating to the smuggling and sale of illicit alcohol.

With Mexico and Canada having no ban, myriad incidents of alcohol being smuggled across the borders became rampant.

The country saw new words being introduced to their vocabulary. Words like “bootlegger” and “rum-runner,” became commonplace. Oddities, like the words “Speakeasies,” “Blind Pig,” and “Blind Tiger” gained common use for illegal establishments serving beer and spirits.

It was a great opportunity for previously small mafia groups to grow and expand their organized crime efforts and maximize profits.

Organized crime factions began popping up in numerous American cities like Chicago and New York, led by men like Alphonse Capone and Lucky Luciano.

Them and others would start raking in millions of dollars by smuggling liquor across the borders of Canada or off the U.S. East Coast.

The demand for illegal liquor was high despite the majority of the nation seeming to adhere to the ban.

Illegal bars sprung up all across the country in the form of speakeasies, which were hidden bars where if you knew the password, you would be granted entry.

The “Roaring 20’s” was going to live up to its name

By 1925, it was estimated that New York City alone had an estimated 70,000 speakeasies operating in full swing.

With the rise of illegal bars, there also came a rise in corruption. Police were paid off to look the other way. Judges were bribed to dismiss cases as they came to trial, and politicians were bribed to look the other way.

The competition to supply these establishments often became fierce among the numerous factions. Gang violence was commonplace, with shootouts taking place on the streets of many American cities as the various gangs sought control of their claimed territories.

Gangster Culture

The American public became enamored with this anti-establishment bravado. Hollywood took notice as well. It didn’t take long for gangster and mob movies to start showing up in theaters across the nation.

They introduced a new generation of movie stars like James Cagney, Edward G. Robinson, Humphrey Bogart, and others to a thirsty nation. This was largely effective with the recent ability to add sound to movies. Audiences were captivated.

But it was real-life incidents like the February 14, 1929, Saint Valentine’s Day Massacre in Chicago that really started to draw the attention of the Feds.

The nation was becoming weary with Prohibition and the lawlessness that grew out of it.

Support began waning on the political front.

The Great Depression

In 1929, everything changed. The world economy crashed. Businesses shut, banks failed, industry ground to a halt, and the unemployment rate in the U.S. surged to 25%.

With so many out of work, the new income tax wasn’t able to bring in nearly enough to support the government.

The push to abandon the 18th Amendment grew. Farmers saw it as an opportunity for grain sales, and many politicians saw it as a revenue stream.

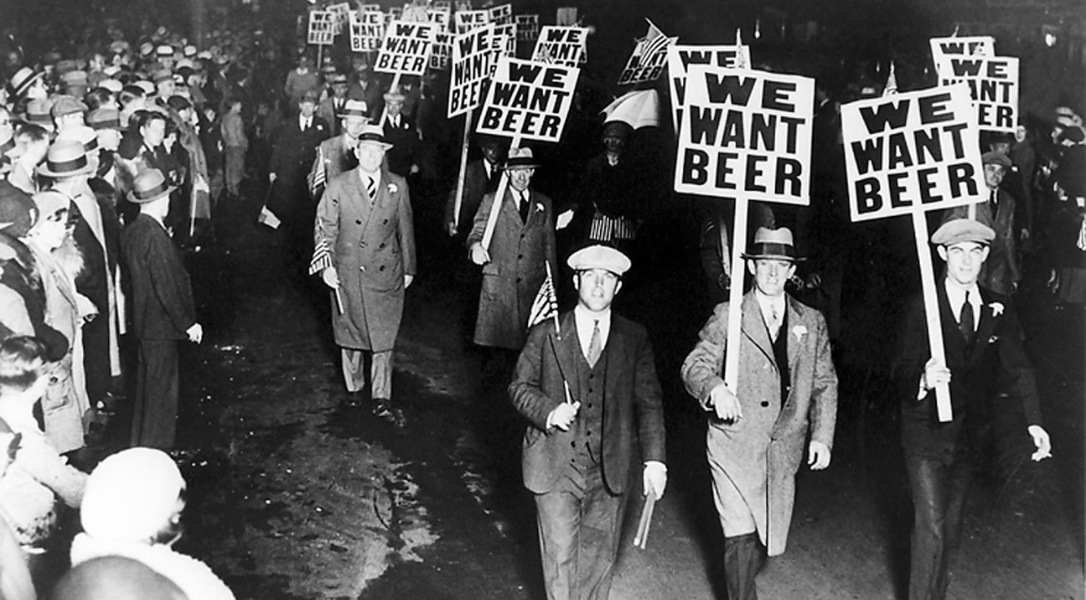

By 1933, the American public had had enough of prohibition and began demanding their representatives do something about it.

The XVIII Amendment was not really viewed as overly successful, although some historians suggest it did cause a drop in alcoholism across the nation. The facts that it had caused a tremendous rise in violent crime and corruption seemed to outweigh that, though.

Repeal

Congress quickly began working on what would become the 21st Amendment. The proposed Amendment passed and was ratified on December 5, 1933, after getting the favorable vote of 36 of 48 states.

To date, the 21st Amendment is the only Amendment enacted solely to repeal another.