While traveling from California to Washington D.C., on horseback in 1854, Senator William Gwin had a hypothetical conversation with Benjamin Ficklin, who was the superintendent of the freight and stage company of Waddell & Russell.

Part of that conversation was the fact that it took almost 6 months to get a letter delivered from the east coast to California.

Gwin didn’t know it yet, but their conversation would eventually lead to the forming of one of the most iconic emblems of American History.

No matter Whose Idea it Was, It was a Good one!

Ok. There are various accounts dating back to 1849 of who really had this “idea,” and the Gwin and Ficklin story is just one of them.

But Gwin and Ficklin were key to bringing the idea to fruition.

Shortly after his journey east with Ficklin, Senator Gwin put a bill before Congress in 1855, to finance a weekly delivery service of mail across the western frontier.

It failed.

In 1858, one of Ficklin’s bosses at Waddell & Russell, William Russell, approached the U.S. Secretary of War, John Floyd with the same idea, a “horse-relay” system.

In December 1859, Senator Gwin suggested that Russell arrange for a demonstration and he would try to get the government to fund it.

Origin of the Pony Express

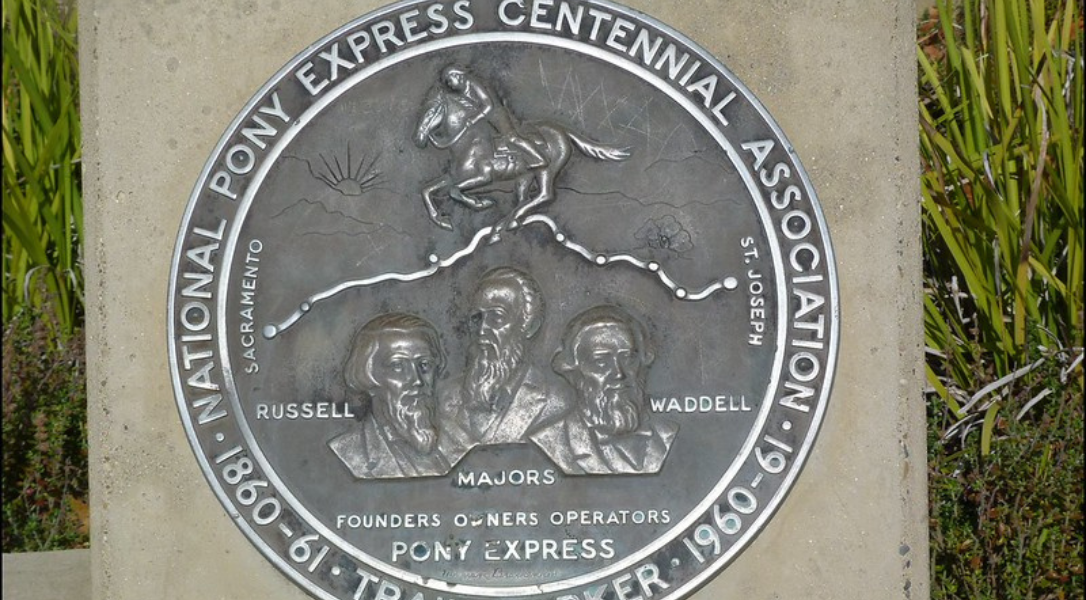

Russell was in Washington trying to get a contract for his shipping company and took Gwin’s proposal back to his partners, Alexander Majors and William Waddell.

Waddell and Majors were mostly against the idea, mostly because of the estimated $70,000 investment they would have to come up with, but they reluctantly agreed to the venture of starting the Pony Express.

Central Overland California & Pikes Peak Express Company

The trio began buying up smaller shipping and express companies for the equipment, began hiring the men, purchasing materials, facilities, and acquiring the 400 or more horses they would need for the riders.

They formed the Central Overland California & Pikes Peak Express Company in January 1860.

On March 2, 1860, they chose St. Joseph, Missouri, as the eastern origin for the Pony Express route because of its location on the Missouri River and it was supplied by railroad coming in from the east and the telegraph lines that ran alongside it.

The destination was San Francisco via Sacramento, 1,966 miles to the west across open plains, river valleys, deserts and snow covered mountains.

And they needed to cross that distance in 10 days, which was 5 days faster than a stagecoach.

Benjamin Ficklin was hired as superintendent and tasked with organizing the route that would leave Missouri, into Kansas, run across Nebraska, Wyoming, Utah, Nevada, and California.

Stations were set up along the route every 10 to 15 miles, about 165 in all.

A rider would cover a 75-100 mile leg of the route before passing on to another rider at a home station.

Riders would gallop from relay station to relay station on a horse with a specially designed mail bag called a “mochila” that could carry about 20 pounds of flat mail.

The mochila was a leather saddle bag fitted with pouches designed to fit over the saddle and the rider sat on it assuring that the bag would not be lost as long as the rider was on the horse.

Once mounted, he rode at a canter or fast trot, 10-15 miles to the next “swing” station, and would in a matter of seconds, dismount, grab the mochila and throw it over the saddle of a waiting horse, mount up, and be off for the next station just under an hour away.

This was repeated over and over until the rider had completed his 75/100 mile leg when he would pass his mochila along to the next waiting rider.

The First Pony Express Run

The Central Overland California & Pikes Peak Express Company announced in mid-March that the first run of the Pony Express would be on April 3, 1860.

A 20 year old local horse racer named Johnny Fry would be first to ride the first leg of the fledgling Pony Express.

Ironically, his 5:00 PM start time was delayed for over 2-hours waiting on an important letter coming via train from Chicago carrying a letter from President James Buchanan to California Governor, John Downey, congratulating him on the launch of the new Pony Express overland mail service.

The train arrived at just after 7:00 PM, and the “49 letters, five telegrams and miscellaneous papers” it was carrying were packed in Fry’s mochila pouches.

Then, amid much fanfare, on the evening of April 3, 1860 at 7:15 PM, a cannon was fired and Fry spurred his mount past the cheering crowds galloping for the ferry to take him across the Missouri River to Kansas.

Once he got off the ferry, he “rode at breakneck speeds for 90 miles” to the first home station where he would pass off his mochila to the next rider.

In all, 40 riders carried that mochila until it reached Sacramento at 5:45 PM on April 13, ten days after leaving St. Joseph.

In Sacramento, all the church bells were ringing, bands were playing, and flag waving people were cheering and shouting in the streets or gathered on balconies and rooftops.

After a ceremonial transfer, a new rider took the remaining mail, packed his mochila and tossed it up on a horse and cantered off for the ferry and the final leg to San Francisco, arriving just after midnight on April 14. It was here that President Buchanan’s letter to the Governor and other documents were delivered along with newspapers from New York, Chicago, and St. Louis that were less than 2-weeks old!

Short Lived Legacy

Russell, Waddell, and Williams had achieved what they set out to do.

A proven mail delivery service from the Missouri River to the Pacific Ocean in 10 Days!

But it was expensive and limited on how much could be carried.

Originally, the cost to use the Pony Express was $5 per half ounce, and with the 20lb on carry weight, meant that the 85 or so pieces of mail costs around $3200 per trip.

The price was lowered to $2.50 six months later, and by July 1861, it was only $1 per half ounce.

The estimated 100 riders were paid $100 per month, costing the company around $120,000 per year.

This meant, on an average, the company needed about 38 trips just to pay their riders in the beginning and over 180 trips by July 1861.

Then there were the myriad expenses of maintaining the equipment and buildings, bringing the costs to somewhere around $1000 per day, or close to $40,000 in today’s cost.

The average citizen could not afford to utilize the Pony Express with the cost to mail a simple letter being $250 greater than what it cost to mail traditionally.

The popularity of the Pony Express and tales of its exciting journeys were glorified in Dime Novels and newspapers back east. Heroic riders braving the elements and hostile Indians became a symbol embodying the American West.

But the real truth was that it was a failing venture.

It is estimated that in its 18-month run, costs exceeded $700,000, and the company only took in around $500,000.

The Central Overland California & Pikes Peak Express Company had been lobbying for a $1,000,000 government contract that they failed to secure.

On December 20, 1860, South Carolina seceded from the Union, putting the nation on the brink of war.

On December 24th, William Russell was arrested by a U.S. Marshall in New York City and was accused of stealing $870,000 in bonds from the Indian Trust Fund and trying to use them to get loans.

He was indicted but somehow saved from prosecution by the chaos of the events surrounding the Civil War, and he was released on a “technicality of the law.”

None of the bonds were ever recovered and the U.S. Government had to reimburse the Indian Trust Fund $759,000.

Technology Kills the Pony Express

While the U.S. Government and the public were focused on the War in the east, the Pony Express was struggling to survive.

Telegraph lines began spreading eastward in from California.

The Pony Express was mostly utilized as telegraph delivery between areas where the lines hadn’t been run, funded by the government.

On October 24, 1861, the nation’s first trans-continental telegraph line linked the country coast to coast.

That same day, eighteen months after it began, the Pony Express was discontinued. Their government contract stipulated in their contract that it was done once the Overland Telegraph Company completed installing their lines.

Modern Comparison?

Much like the USPS today, the Pony Express was originally a good idea that became a waste of taxpayers funds.

Our 19th century government recognized the futility of the cost of maintaining the Pony Express.

Our national mail system was reorganized into the USPS by Richard Nixon in 1970, establishing it as a stand alone federal agency.

In 2006, legislation was passed that the USPS was required to become self-financing, which included pre-funding its retiree and health benefits.

In 2006, legislation was passed requiring the USPS to pre-fund retiree and health benefits for employees.

The U.S. Treasury department supplied the funds until the USPS became profitable, and after 6 years, it was mandated that the USPS repay them.

In August 2012, the USPS missed a $5.5 billion dollar payment for that loan.

The USPS then defaulted again in September 2012 on another $5.6 billion dollar mandated payment citing loss of income.

Donald Trump has Elon Musk and DOGE evaluating the problems within the agency that make it such a huge money pit.

Of course, the Left is screaming as DOGE suggests making staffing cuts and figures out how to increase efficiency.

Trump has also stated that he is not against the idea of privatizing the nation’s postal services that could potentially save taxpayers billions.

Like the Pony Express of old, maybe it’s finally time to let the USPS ride off into the sunset?

Are you enjoying 24/7’s deep dives into recent and not-so-recent history? Would you like to see more stories like this one? If so, send a note to news@247politics.net and let our Editorial Team hear from you today!

Keep an eye on your inboxes every Thursday and Saturday for new editions of “Today in History” from the 24/7 team!